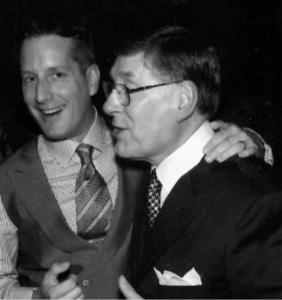

Brad Lamm gets people into drug recovery by asking, not threatening.

By SAM MILLER

The Orange County Register

The four Lamm boys had a mantra: “I don’t drink, I don’t chew, and I don’t go with girls that do.”

They were the sons of the senior pastor at Friends Church in Yorba Linda. Brad was the

youngest, a scholarship kid at a nearby Christian school who offset tuition by washing buses after school.

But at a party one night, when he was 15, he drank a Bartles & James wine cooler.

“I immediately wanted more,” he says. “It wasn’t about fun. It tickled something in my brain.”

Brad kept repeating the family mantra long after he’d stopped living by it. He moved on to meth and hallucinogens. When his parents confronted him, he was a comfortable liar. He kept it together long enough to be junior and senior class president, then he bolted from Yorba Linda for two decades of addiction.

Tonight, at age 43, he’s back in Yorba Linda for the first time. And he’s on a mission.

…

It’s been 40 years since the classic “intervention” was developed. The script is familiar. The addict is tricked into the appointment. Family and friends read a list of grievances, demand the addict give up drugs, and threaten him with consequences – stop

drinking or you’ll never see your children, for instance. This is what’s called the Johnson Model of intervention, the dominant method since the 1960s.

In recent years, though, the Johnson Model has gotten competition. Some interventionists have tried to make the process gentler, more supportive and less deceptive – a process called an A.R.I.S.E. intervention. Instead of ambushing the addict, they say, loved ones and interventionists should invite them to the intervention. Why begin a process of trust and love with a lie, they ask.

“One of the criticisms of the Johnson Method is it tends to be coercive and can produce a real rupture,” says Richard Rawson, an associate director of integrated substance abuse programs at UCLA.

“The whole field of addiction treatment which had a huge emphasis on confrontational treatment (has been) revolutionized. You don’t beat people over the head with their addiction, and yell at them and tell them they’re in denial. You work with them on their ambivalence to get them into treatment. The system is more human.”

Still, the Johnson Model is dominant in pop culture. It’s become common on TV shows, and the A&E network has turned it into a reality show, where addicts – sometimes minor celebrities, sometimes the crack addict next door – are ambushed.

“I’ve been doing this a long time and I still kind of scratch my head as to why the Johnson Model is practiced,” says Kristina Wandzilek, executive director of Full Circle Intervention, which uses the non-confrontational approach to interventions.

…

Twenty-five years after that first wine cooler, Lamm finds himself in the center of the dispute.

When he was 35, Lamm got a job as a weatherman for a Fox affiliate in Washington, D.C. He didn’t show up regularly, and reeked of alcohol when he did. His skin was yellowish, his liver was so damaged that his abdomen was distended, and he was drinking about 15 drinks – “big drinks,” he says – every day.

“It was evident to anyone around me that I was having a hard time,” he says. That includes his bosses, who fired him after just a few months.

At that point he had been drinking for 20 years, using cocaine regularly for 15, mixing in

Methamphetamines in short stretches. But he’d never been in the middle of an intervention.

When he got fired by the TV station, four of his friends invited him to talk about his drinking. They invited him to make some changes, starting with three months of therapy and daily AA meetings. He would try to stay sober, he would fail, and his friends would meet with him again, in person or by speakerphone.

After six months, they told him he needed more treatment. “I don’t know if they’d even call it an intervention,” he says. “Lead with love, don’t take no for an answer, and leverage the love that exists already.

“I showered and, within 18 hours, I was on a plane to California.”

He entered a treatment facility in Laguna Beach in early 2003. He’s been clean ever since.

…

OxyContin. Her parents were worried about her, so they called Brad. The parents flew up

from the southeast; the woman’s grandparents flew down from the northeast; and Brad, who lives in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, called the woman.

“Your folks are in town,” he told her. “They’ve been talking about how scared they

are. I suggested a family meeting.” She was shocked, but she agreed.

At that point, he says, the intervention had begun. “We are not going to solve the problems tonight. Our goal is to get her to trust us just enough to help her,” he says. He’ll work with her family, hold weekly phone conversations, and help chart family histories. It will continue for months, if necessary.

He opened a private practice about five years ago, Intervention Specialists, and has done about 400 interventions since then. This winter, St. Martin’s Press is slated to publish his first book about his kinder, gentler interventions.

“The family’s baseline is always, ‘We have to trap them, like an animal,'” he says. “I always have to talk them into making an invitation. I tell them, there’s a place inside you that can either be occupied by fear or hope, and it can’t be both. We get better results with hope.”

For 20 years, Lamm’s life was nothing but fear. He says his grandmother was an addict who spent part of her life in an Oregon mental institution – the one made famous in “One Flew Over A Cuckoo’s Nest.” His grandfather, he says, married six different addicts, before dying of a prescription drug overdose while gardening.